This opinion piece was original published by The Baltimore Sun on September 23, 2025.

As children are back in school here in the United States, the fate of millions of children worldwide who benefited from U.S. investments in their basic education remains unclear. Recent estimates note that the number of out-of-school children worldwide stands at 272 million, and the number is likely to rise as global education funding faces steep cuts.

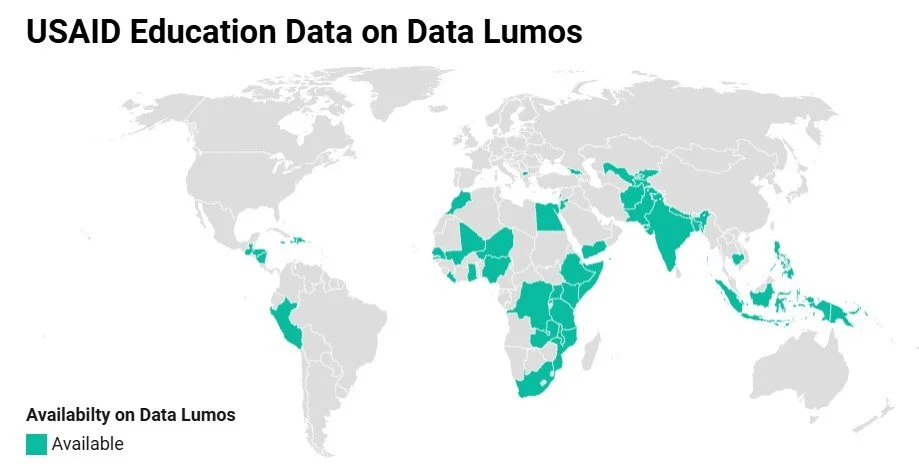

On July 1, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) shuttered its doors and any remaining foreign assistance programs were transferred to the Department of State. Yet there is uncertainty about whether and where international basic education programs will find a home, despite

What we do know is that 163 of 165 education programs previously funded by USAID have been terminated. The two that remain – both in the country of Jordan – are having an incredible impact on the children and communities that they serve. This includes providing over 23,500 early-grade teachers with enhanced curricula, teaching and learning materials, and assessments that will increase the learning outcomes of over one million students over five years.

These are the kinds of life-changing interventions that more than 44 million learners around the world – many of them in vulnerable situations – used to receive before USAID disappeared. The U.S. Government’s FY23 Report to Congress on its International Basic Education Strategy provides details about this support including how students in pre-primary, primary, secondary, vocational, and workforce development programs benefited from U.S.-led programming.

We all recognize the importance of investing in a young person’s education. Not only does it benefit them personally, but it helps towns, cities, and countries by equipping society with the human capital needed to thrive. When our neighbors and partners succeed then we, in turn, as a country, benefit. We have more trading partners, other countries can share the burden of responding in times of crisis, and the world becomes safer and stronger because countries have the tools they need to contribute their share to the global economy

While every year of learning generates about a 10% increase in earnings annually for a student, the true value of education extends well beyond financial returns. It broadens the spectrum of individual choice, facilitates the transmission of societal values across generations, and enhances the quality of life. Many countries want to invest in their educational systems but have to make hard choices with limited resources. A helping hand during these trying times can make a world of difference, paying off both for students who see their futures full of possibilities as well as U.S. foreign policy goals.

There is a long road ahead as the U.S. determines how it will approach foreign assistance in the future. Yet, we see two glimmers of hope. One is that Congress has not given up on endorsing these investments. Indeed, the House of Representatives released its draft budget for Fiscal Year 2026 and included $737.6 million for international basic education programs. While this amounts to a decrease of almost $200 million in funding from the previous year, the message came through loud and clear: Education remains a priority.

Second, Secretary Rubio recently appointed a new Special Envoy for Best Future Generations who will serve as a liaison for initiatives impacting the well-being of children both in the U.S. and globally. While specific authorities and activities are yet to be defined, this sends a signal that the U.S. still considers children and youth a necessary priority.

Now is the time to leverage this momentum and ensure that the U.S. continues to champion the transformative power of education. We must build on past investments and successes, not retreat from them. Congress must make its stance clear: The U.S. values international basic education and will continue to fund it accordingly.

We must remember those children who won’t be walking into a classroom this year. For them, school isn’t a given, it’s a dream that would allow them to achieve their full potential. And with U.S. foreign aid for education under threat, that dream is slipping further out of reach.

BEC and Global Campaign for Education-US have long collaborated on advocacy for international basic education — a uniting of voices that is now more critical than ever. Giulia McPherson is the Executive Director of the GCE-US, a broad-based coalition dedicated to ensuring universal quality education for all. She has 20 years of leadership experience in the humanitarian and development sectors.